Raised By Spielberg

He may not know it, but Steven Spielberg was my second dad

“This is a story of instinct. Those of an apex predator. Those of a Hollywood studio. And those of a director, who defied the elements. No one could have foreseen the profound effect it would have not only in film but culture, becoming this Jungian wolf whistle. Bah-dum. It’s a holy text for a generation of filmmakers…”

Steven Spielberg: The Iconic Filmmaker And His Work

You can count on this. Next year there will be books, re-releases, parades, and probably beach parties. Jaws is about to turn 50. Set aside the standard Easy Riders rubric of spoiling all that seventies art, the film was a tipping point in culture.

An art film with bite, a monster movie that moved people. Do we really blame it for being so popular? In ready terms, this anniversary is as profound as the heritage of Citizen Kane. It’s certainly the most significant film in Spielberg’s career - the one that gave him the freedom to become Spielberg. Nothing was the same after that.

Spielberg still recalls the nightmare of its making, his memories are less temperate than mine: the uncooperative elements, the infernal currents, the incessant wind, and the damn mechanical shark, boss-eyed in the drink, driven by air-pressured tubes like some dystopian contraption from a Terry Gilliam flick. Corroding in the salt water, limpets clinging to a polyurethane belly, the malfunctioning star was the making of the movie. Imagination took his place: Spielberg’s, John Williams’, our own. You could say, Spielberg’s talent took the place of a great white.

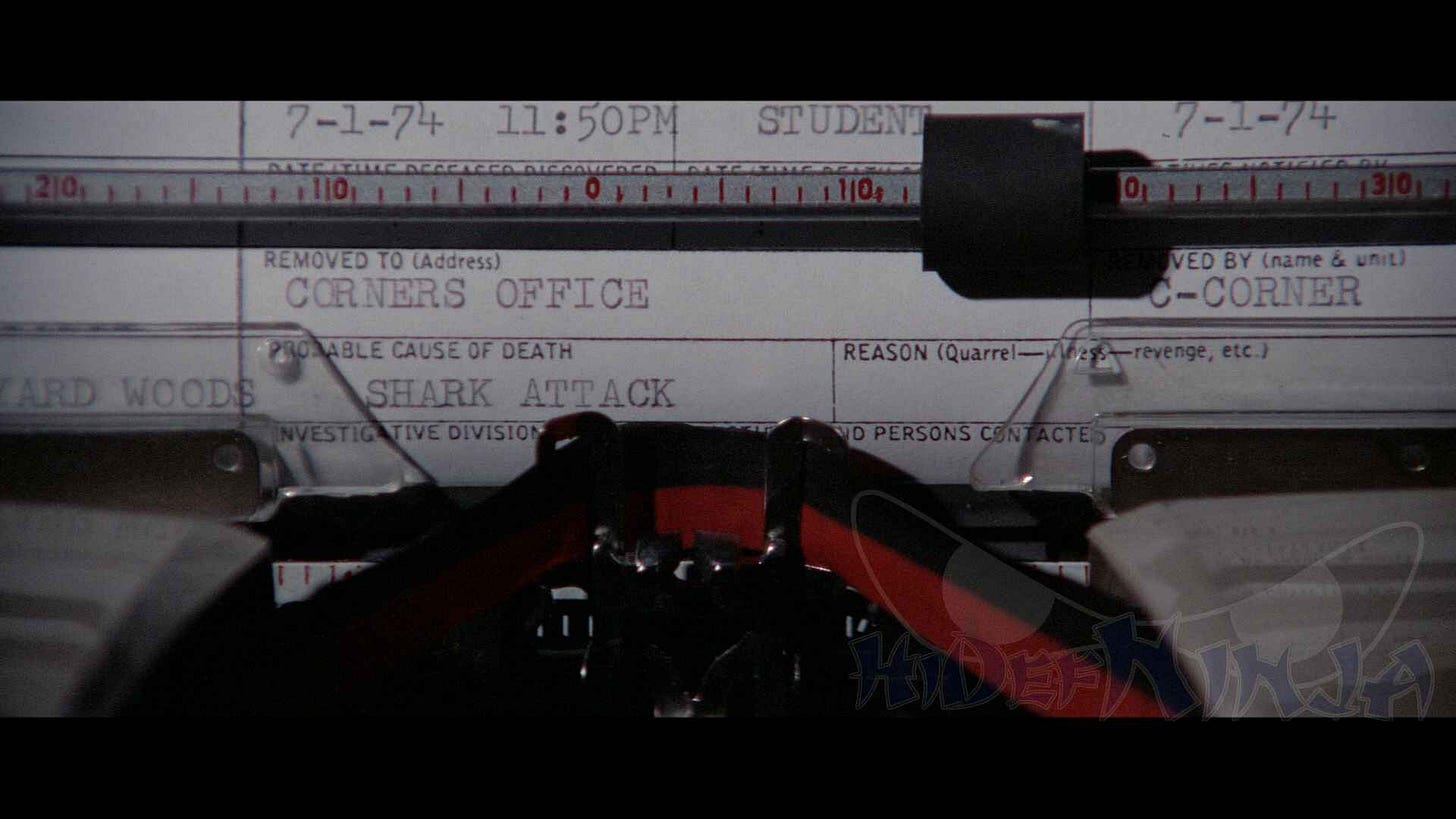

We never forget the Chekovian image of oxygen tanks in the teeth of a shark in Brody’s book, the surfacing of the yellow barrels, the distant cries of an orca, or Brody typing “shark attack” on a quotidian police form.

There is so much to the story of this film, so much beautiful craft. Nearly a half-century later, and we’re still not talking about Jaws enough. I truly recommended reading Antonia Quirke’s BFI Classic on the film’s meaning, combined with screenwriter and erstwhile actor Carl Gottlieb’s Jaws Log, the definitive guide to what happened on set. Both were a priceless resource for me.

Here’s my point. I was too young to have seen Jaws in the first wave, yet the film is so familiar to me, so cherished, it is an integral part of who I am. Early Spielberg is like that - films that have become memories. I sulked all day as an eleven-year-old until my parents took me to see Raiders of the Lost Ark - I simply couldn’t cope with not seeing it. That event has made more of me than every exam I have ever taken.

“This is exactly what happens when best friends get together to plot and play to their hearts’ content. A sandpit spectacle constructed from sheer verve. Shot by shot, moment by moment, iconic image by iconic image, Raiders is the Spielberg recalled better than any other.”

Steven Spielberg: The Iconic Filmmaker And His Work

So many entries in his storied canon are resident in my cerebral cortex like the replicant fail-safes of Blade Runner or Christopher Nolan’s implanted ideas in Inception. It’s one of the themes I have aimed to capture in my new book: why the experience of watching Spielberg’s films changed us in some way. They were experiences by which others would be judged. These were films by which others would always be found lacking, sometimes even Spielberg’s. He’s always had to wrestle with that.

With a career as long and illustrious as his, anniversaries, commemorations, the tide of think pieces and reunions, is a yearly occurrence. Last year, 2023, marked 30 years of Jurassic Park and Schindler’s List. Next year also signals The Color Purple’s 40th, Spielberg’s conscious (if slightly illusory) shift into the adult. This year the pipes have stayed relatively quiet on four decades of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom - maybe because of its awkward reputation and even the director’s ickiness at the recollection. I still loved it, and love it still. The camera gliding through the mine populated with enslaved children to rest on Harrison Ford’s face, ironic smirk and bruised ego replaced by pure, determined fury. I had my own parade.

So I have written a book - the book maybe, in terms of my memories. It is part of my successful Iconic Filmmakers series, but in thinking about Spielberg’s films again, beneath the cover of analysis, history, appreciation, and the ready store of anecdote, evolved the most personal thing I have ever written. These films are a part of me. And I know I am not alone in that. Our relationship with them is primal. I say it a lot, but I have never understood the description of E.T. as feelgood. Has anyone departed Spielberg’s central film with their heart still intact?

“A tale of science fiction held as softly as a child’s hand, his little experiment would become one of the most beloved films in history. Proof that Spielberg’s gift was an elemental expression of story, a form of emotional communion. Like Elliot and E.T., he felt our feelings.”

Steven Spielberg: The Iconic Filmmaker And His Work

Over the years, things have changed, I’ve changed, and Spielberg has changed. Still more than worthy of their anniversaries, later films became more bracing, even shocking, darker in more tangible historical ways. Schindler’s List is extraordinary not simply for what it dares, but the way in which it tells its story - watch it again, less as a devastating document, but as a sublime piece of storytelling shifting in register from documentary to Chaplin to film noir. Munich is growing in stature. Lincoln is a marvel. Lately, Spielberg has gone a little under-appreciated.

But it’s those first ten years that shaped me. And Jaws reaching 50 is a salutary as well as joyous occasion. Have I grown old? Why then do I feel no different from the day I saw it? At least, on the inside. If you are following me on Twitter (or X or whatever it is: @iannathan2), or indeed Facebook, I’d love to hear your Spielberg memories, or feelings, or just scenes that you love the hell out of.

Meanwhile, I hope you enjoy my book, it’s about you as well.

Fin.

Steven Spielberg The Iconic Filmmaker and His Work is out now.